A Comedy of Errorsand Education (in Yoruba)

The Host

Guru Ramanathan

Hello and welcome to Found in Translation.

I'm your host Guru Ramanathan.

And this is a podcast where people who are first/second generation and/or immigrants come on to talk about their relationship with their cultural language and how that's influenced their connection to their culture, family, friends, and more.

This week's guest is Michael Oluokun, a close friend and one of the funniest writers and comedians that I know. Michael and I were in the same program at NYU and even co-hosted a podcast for a few years with some other friends of ours.

This is Michael

But now he's on the other side of the mic, and here to talk about

A)navigating his Nigerian identity

B) hilariously uncovering Nigerian customs at family parties

C) learning the language Yoruba in college

D) and how his writing and performances have been shaped by this journey.

So, hope you enjoy!

~ interview begins ~

How does it feel to be a guest instead of one of the hosts?The Guest

Michael Oluokon

It's pretty chill because now I don't have to think about like, "Oh no, am I asking enough questions? Am I giving the guest enough space to talk?" I can talk for as long as I want.

Well, yeah, I mean, this entire episode, it's your space, it's your time to shine. We're also gonna start this one at the very beginning. It's interesting to think about what your connection to your language was right when you were pretty young and seeing how that's evolved over time.

I'm so curious to hear from your perspective, being the youngest of four siblings, and I know your mom also came from Nigeria. But just to begin, what was your connection with Yoruba in your childhood and how did it play out when you were growing up?

Yeah, when I was younger it was the language that my mom and my Nigerian relatives would speak, but that we just would never really be in on.

My mom very deliberately decided not to teach me or any of my siblings Yoruba, which was an interesting choice. But... I respect it, but, you know, sometimes I kind of wish I would've been taught it.

There were different points where my grandma lived with us when I was younger, so they would speak it to each other. But none of my siblings were ever taught it.

I got familiar with the sounds of it, but I never learned vocab or diction or grammar. And I even learned, like, my name isn't pronounced the way I think it was pronounced. But then that was also an intentional thing on my mom's part.

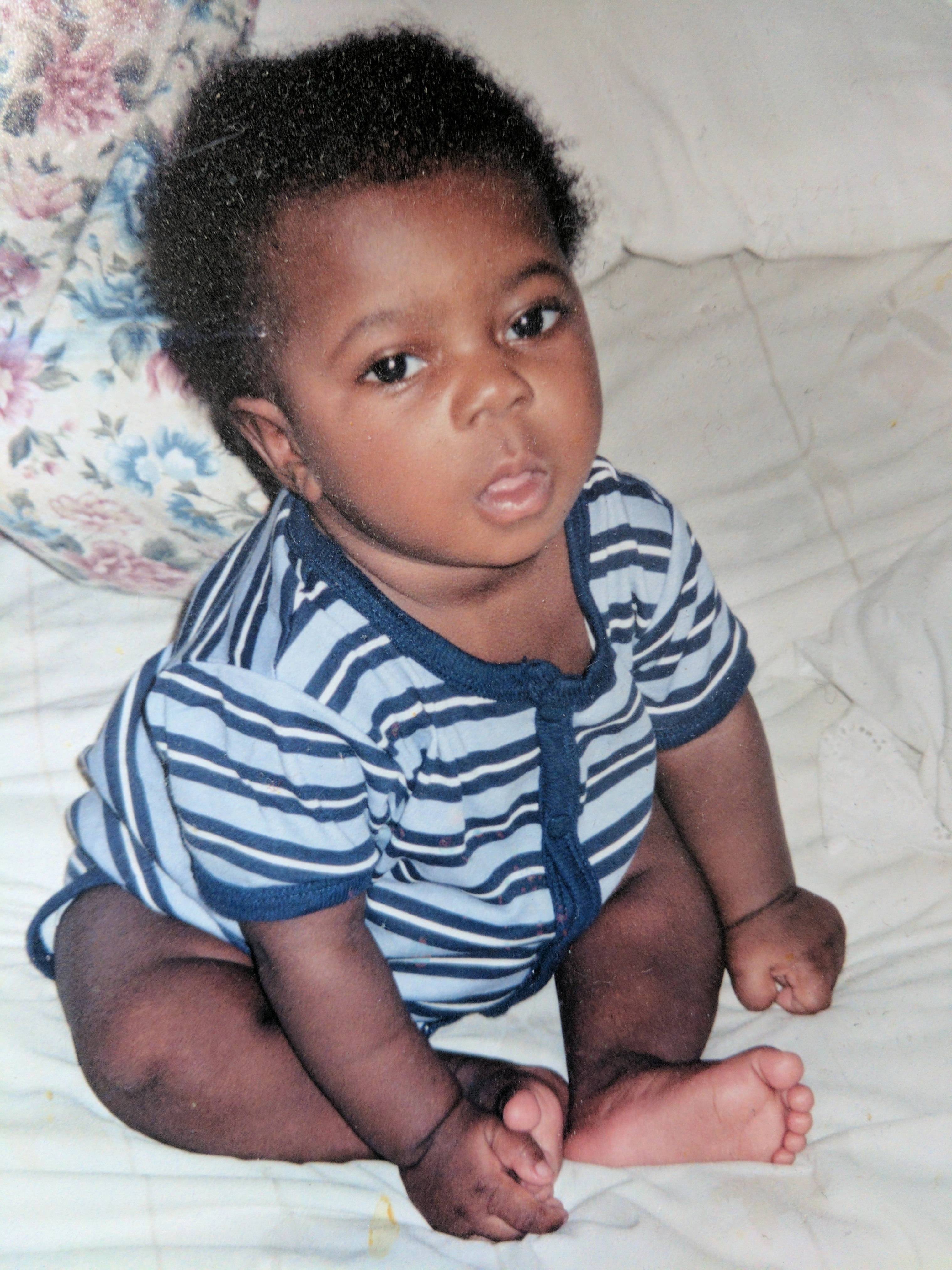

This is baby Michael

For lack of a better term, assimilate better.

She wanted us to be fully American.

We had a lot of relatives who were in the States, so a lot of them kind of congregated in the D.C. area. There's a pretty big Nigerian community in the Maryland-D.C. area, and so I had a lot of aunts and uncles who lived there.

We would go to Maryland for a week for holiday. There would be a big party where there's a bunch of Nigerians invited.

And, you know, the two levels of the party were adults, who are usually from Nigeria, and then their children. Some might have been born in Nigeria and then moved to the States at a young age. And then some were born in the States, but they might have had some level of fluency in Yoruba. So it's interesting, each person's experience was a little different.

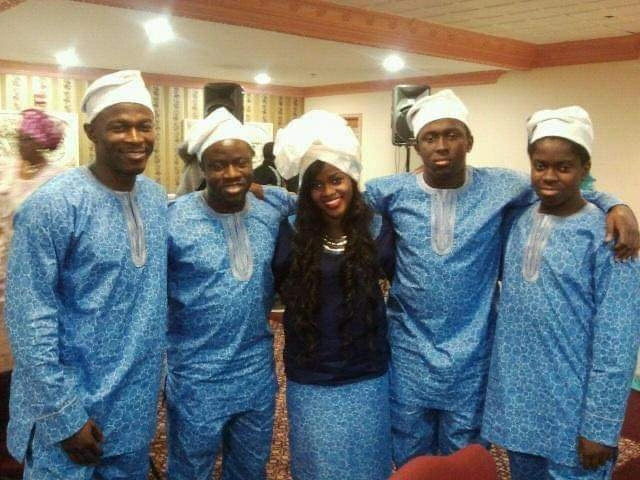

This is Michael's Family

Because I've definitely had some of those parties come around. But then, there's a bit of a hierarchy as to who can communicate in the multiple languages. Or, the parents always talk about, "Oh, your kid does so well here, but I wish mine could too." Was there that sort of internal prejudice around those who were better at Yoruba than others?

To an extent. I wouldn't say it was ever super-super bad, but it would always kind of come out in the...

"Oh, you don't know you were supposed to do this?"

"You said that so American. Wow, you really aren't Nigerian."

It was almost club-type exclusion.

I remember, distinctly, one time. It was my grandma's 80th birthday celebration. And we had this huge event. We had a whole bunch of relatives and family members and it was this big party.

And then, you know, all of her children spoke and then they were like, "We got to have all the grandchildren speak, too."

We weren't primed on the speaking. And so, it was basically American children in front of this panel of judgmental Nigerians.

And, you know, we're going up and we're like, "Yeah, happy birthday, grandma!" We're saying our last name wrong. And then cousins come up and they're saying their names perfectly pronounced. We got set up here!

But it was always that kind of experience of you walking into a situation where you're like, "Oh, like, this is gonna be fine!" And then something happens and you're like, "Oh, it's not fine. I'm confused." Like you're looking to your parent: "Why didn't you tell..." There's obviously something not being communicated.

Michael and his family at his grandma's 80th birthday party

I remember one time we went to an aunt's house and like, there's a custom with certain Nigerians where you're supposed to bow upon entry. That's a custom in a lot of different cultures.

And we had one aunt in particular who was really stringent about that. But, you know, all of us as children didn't know that. And the phrase for you to bow is called "dobale." We show up to the house and we're just like,

"Oh, hey what's up auntie?"

Her name is Joké, so we're like, "What's up Auntie Joké?" And she's just like,

"Dobale!"

And we're like,

"Huh?"

She's like,

"Dobale!"

And we're like,

"Ahhh!"

And then my mom's like,

"Oh, you're supposed to bow."

I must have been no older than eight or nine. I'm just like,

"Bow? Like, what, like--"

She's like,

"Get on your knees!"

I'm like, "Okay!"

But it was like, I know you can react to it in two different ways. It's like, "Oh, that was kind of crazy in the moment, but isn't that a funny story?" But, I feel like sometimes people can kind of get a chip on their shoulder because of that. It's funny, my mom herself, who grew up in Nigeria, she's always like, "These Nigerians!" She always phrases it like that.

It's interesting because I've heard my parents talk in that third person perspective of, "All Indians are like this, all Desis are like this." And then growing up I didn't really understand -- but like, you're also that, so you're hating yourself.

I think I get it more now that I'm older. I feel like people just love to be able to talk about a group as a whole. They're like, "Man, I've seen at least three people do this. So I've got the data set I need, you know?" Part of me thinks one of the reasons she decided to move from Maryland-D.C. was almost to get away from large numbers of Nigerians.

She's expressed this to me that like, you know, sometimes being around very traditional Nigerians can be very frustrating to her. And especially if you, like, really, really grew up with it, you just want something different, you know. My two oldest siblings have been in Nigeria, but me and my brother closest to me have never been.

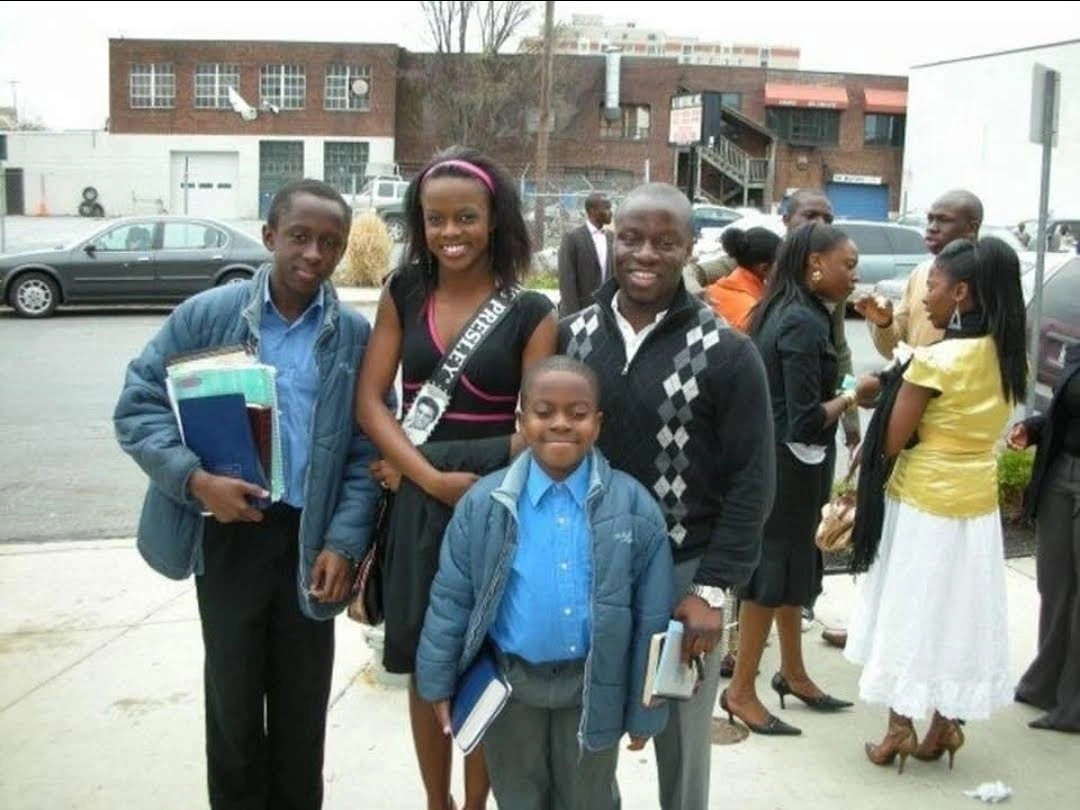

This is Michael and his siblings

They actually spent a whole year in Nigeria and went to school there for a year, and then came back. I've never actually asked my two oldest siblings about how that experience was for them. Sometimes my mom would talk about it and was like, "They came back with a chip on their shoulder. Now, they're not Black, they're Nigerians, you know?"

And then, when you were growing up, were there other Nigerians in school or were you predominantly just around American Black kids?

In my most recent Arkansas church, there were a few other Nigerians there, just like out of the blue, which was interesting. But, my school was really white.

Even just Black people at the school, like, you could count on two hands the number of Black people in my grade, you know?

What were your feelings about not knowing Yoruba, given the fact that your mom wasn't really pressuring you, your siblings didn't know it either, and then you weren't around a lot of Nigerians in school. Was it something that you thought about, not knowing the language, or was it something that was more of like a distant connection?

It kind of was a distant thing of like, this is this thing my mom does. When I was a kid, especially being the youngest kid, there are a lot of people telling you, "Don't ask a question about this." And I'm like, "Okay."

Since the only person that knew it was my mom, and like, you know, my mom was kind of someone that like, "Why are you asking me questions?" Like unless you were like, "I need to go to the hospital," she's like, "Don't ask me." You know? And even then she would be like, "I'm a doctor. Let me see."

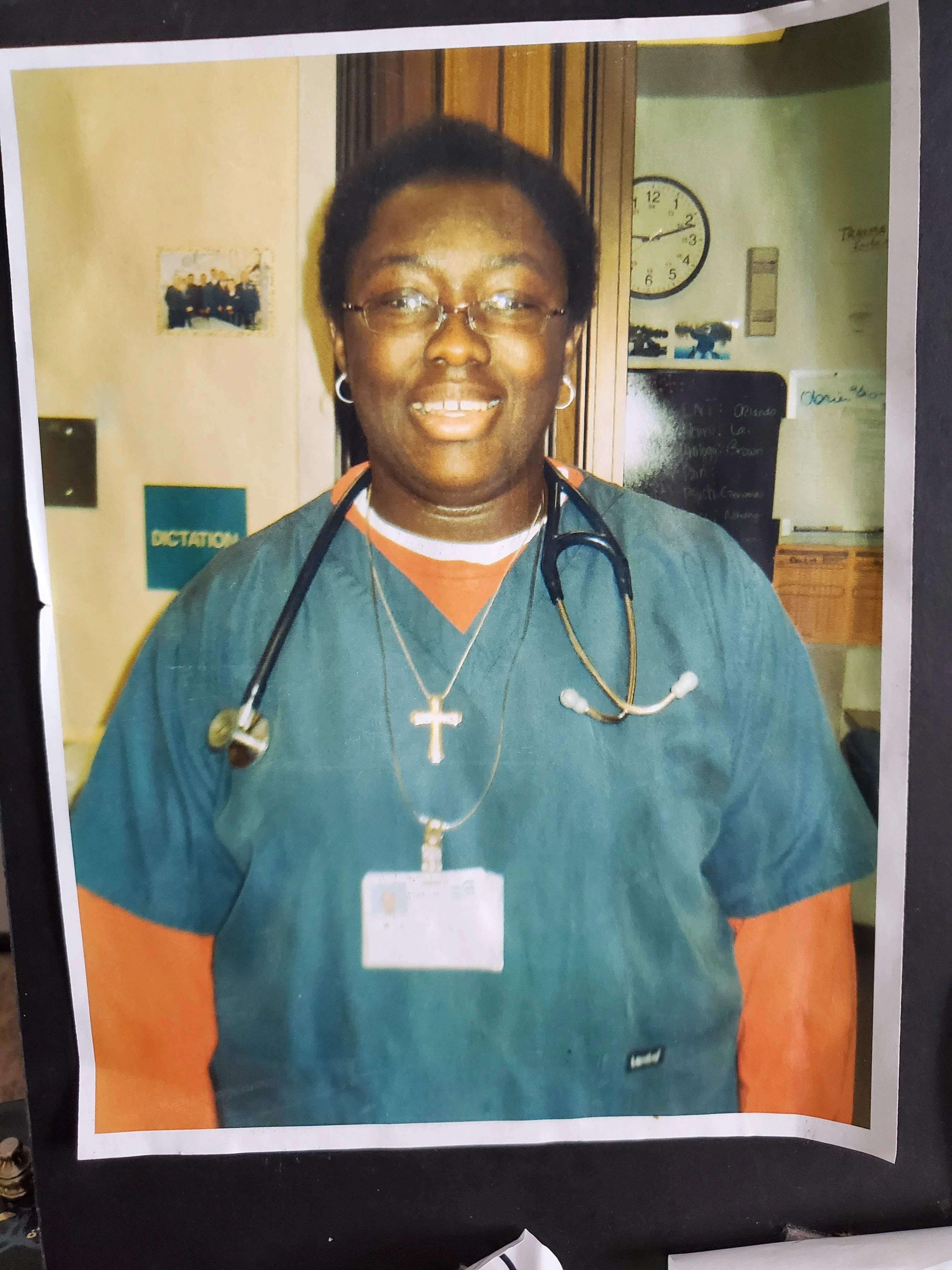

This is Michael's mom

I've always been interested in learning languages. I was always really fascinated by linguistics, and I would always try and look at the IPA pronunciation guides. And you're trying to learn how to pronounce the word in another language and you click on it, and it's like an upside down G and, like, an S with a slash through it. Like, how am I pronouncing this word, you know?

I always wanted to learn more languages, but when I was in school, the only foreign language they really offered was Spanish. There's a point where we had a French teacher and then the French teacher left, and then they were just like, "Yeah, we just don't have French anymore. You can take French 1 online." Coming to college, I really wanted to learn French. French is always such a chic language. And you know, I even justified it because so many African countries speak French. French is one of their top three languages. Especially West Africa, it could even serve me there.

But then I was looking at French courses and I'd almost signed up for this six-credit French intensive. And I was like, you know, "I'm just gonna really learn French." And then I saw that they offered a Yoruba class. I never even thought of the idea that I would be able to take an elementary Yoruba class.

It fit with my schedule and it was four credits, so it was like, "Oh, I wouldn't have to really just kill myself to take this foreign language." The six credit one, it would've been, like, every Monday through Friday we had to meet.

I was like, "You know what? When am I ever gonna get the chance again to take an elementary Yoruba class?" So, I decided to sign up for Yoruba 1, and it was cool. It was cool to have a class of mostly Nigerians, but there were also a few non-Nigerians. Because, interestingly enough, there is a Yoruba diaspora in Latin America, and so there was a non-Black Latino in the class who was from the Yoruba diaspora, which was interesting.

This is Michael in college

I'm fairly certain it was sophomore year. Yeah, it definitely wasn't freshmen year. I think it had to have been sophomore year because junior year was when we got kicked out for COVID. Because there was even the option of taking Yoruba 2, but then I would have had to commute to Columbia to take this course. So I was like, nah.

She was definitely really happy. She's like, "Your grandma's gonna be really happy about this." Because my grandma still speaks a lot of Yoruba and Yoruba is a very personal language for her and my mom. To say a few words of it together -- it made her smile, you know?

Yeah! When you start to tap into the language, then it opens up the floodgates of, oh, let me now try to watch Nigerian movies. Let me try to listen to the music more regularly.

Let me try to do X, Y, and Z more and more. Like going to Nigerian restaurants and order in Yoruba. Did that class change the way you perceived your Nigerian identity or evolve you forward in any way?

I definitely think it did evolve me forward. One, it encouraged me of, you know, it's okay to not know Yoruba because it doesn't make you any less Nigerian than others.

Especially when I was younger, I always had that chip on my shoulder of my mom's Nigerian, but I don't feel like I can really consider myself Nigerian because I don't speak the language. I've never been to Nigeria.

And tying back to another thing you had mentioned earlier with your last name, How did that... I don't know if I wanna call it a revelation or, like, a transition or however you want to put it, but how did that change?

Yeah, I feel like it kind of put a lot of things into focus for me. You know, every time we would say it in a large group of our relatives, me and my siblings would always get clowned. They would be like, "Oh man, like these kids are not Nigerian at all." You know? It never clicked to me that we're literally pronouncing our last name wrong.

And it's interesting that my mom chose to tell it to us that way so it was easier for white people to say, but then it still was always mispronounced. And so, I'm like, "Well we might as well have just said it the right way. It actually didn't make any difference.

This is Michael and his comedy crew

When and how did you find out?

It was when I was in that Yoruba class.

Oh, really?

Yeah. There's like a few different vowels in Nigeria. And certain vowels you can nasalize. You nasalize a vowel by adding a N to the end. I learned about how each of the vowels was pronounced, and I was like, "If I pronounce this like, how, with each of the vowel rules you just taught me, like it's pronounced like this." And he's like, "Yeah." And I'm like "Oh! I've been saying it wrong."

My teacher would always ask me, "What state in Nigeria are you from?" And I'm like, "Oh, I don't really know." And he's just like, "You don't know?!" I know, he was always like, "Go ask your father!" And I'm like, "Oh, my parents are divorced." It's like everything I said to him, he was just like, "Ohh no!"

Yeah, since then, I haven't really kept up with my language practice. You know, I don't know that many Nigerians in my personal life. I feel like I always meet Nigerians randomly, and it's like... They're always inviting me to church. Yeah, for sure, I'm gonna wake up at 9:00 AM on a Sunday and take an hour train to the Bronx so I can go to church. You know, it's like, oh, I don't wanna do that. But like, I do want to meet more Nigerians.

There are definitely Nigerian comedians, but there aren't that many at my level right now.

Yedoye Travis. He's really big on Twitter and he's been getting bigger in the standup scene. He has a 30-minute special on the Comedy Central stand-up YouTube page. And, I know he wrote a Batman comic.

Oh wow!

Yeah, and he was working on "Saved by the Bell," too. And so he's kind of like a current, young Nigerian comedian/writer who's kind of like-- I'll phrase it as a Donald Glover disciple. One of his jokes is that he describes himself as Donald Glover's Wario.

And then, Ayo Edebiri. I'm pretty sure she's from, if not Boston, Massachusetts for sure. And she also went to NYU. She's in "The Bear," and she's been on a lot of other shows. She was on "Dickinson."

But yeah, there's a lot of cool Nigerian comics out in the scene, but it's just like, I'm still in my... I'll phrase it as my indie darling phase. So I'm like, you know...Maybe one day... Once I get nominated for my Golden Globe, then I can reach out to these guys.

Yeah. I wanted to touch on your comedy and your writing, and such. How has interacting with these Nigerian comedians, your family, starting to immerse yourself in Yoruba, influenced your artistic identity? Or, has it changed the way you write or the things you write, or what you like to bring up in your standup? What's that evolution been like in your artistic journey, too?

Yeah, I feel like it's definitely influenced the way I write and the way I do stand up, too. One of the interesting things about Yoruba as a language is that it is a tonal language. And so, the way you say things influences the actual meaning of it.

I just remembered another Nigerian comic. His name is, I think, David Gborie. And I noticed it when I was watching his standup. The way that he used the tone of his voice was very dynamic. I wonder if that's a function of him being Nigerian. Even if you don't speak Yoruba, there's an animated way of speaking that Nigerian people often use that influences you even if you don't speak the language.

The way Nigerians speak English is its own thing, you know, so influenced by British English. But if you grew up in the States, but then your parents grew up in Nigeria, and then depending on their parents, it's like some of them have more of a British influence, and then some of them have more of a strictly Nigerian-Nigerian influence. And then some of them might even have more of a French influence. So it's interesting the different influences, the sub-influences, that then go into the influence that then makes you speak the way you speak.

Especially as a writer, I'm always so fascinated by the rhythm of how people speak. Sometimes you'll be writing a line, and you're just like, "This just isn't working." And then you'll just move one word and you're like, "Oh, that's perfect."

And it's like, sometimes it's that subtle, the difference between, this is how a Nigerian would say it versus this is how someone from New York would say it.

Sometimes I feel like it frees me to express the idea the way it sounds in my head versus how I think it should sound, you know, as a standup, you know? The interesting thing about standup is that it's just you up there. You're up there being yourself and you're just telling jokes. But to do standup, you kind of have to embody a persona. And sometimes the persona is just you, but sometimes the persona is a fragmented version of you. Or like, sometimes you're playing off of an archetype that other comedians before you have established.

So it's like, how much of it is you trying to play to the archetype that you think people see you as? Or, you trying to just authentically say what sounds funny in your head, you know?

And I've heard people sometimes talking about how, when they speak in another language, sometimes their personalities can like slightly shift. Were there any shifts like that in the way you thought about things, or the way you acted when you were physically trying to talk in Yoruba versus English?

I feel like I didn't really experience any large personality shifts, but it made me think about things in a more Nigerian way, in certain aspects.

Like in Yoruba, greetings are a really big thing. One of the first things we learned was greetings because there are certain greetings that you're supposed to use for the different times of day. And then there's also different greetings that you use for different levels of, like, if you're greeting your friend, you can say this. But if you're greeting an elder, you should say it like this, you know? And so, it's interesting there's different levels to the same word and the same function, but the situations that you're allowed to use them in are different.

And then you have to go through your rolodex. It's like, "What time is it and what's my relationship to this person?" And so it's, yeah, it's just the fact that you have to consider a lot of things before you speak is a thing that I was thinking of a lot more when I was taking the Yoruba class.

Yeah. To my understanding -- I could be totally off base about this -- but to my understanding, like, in Africa itself, I believe the Nigerian entertainment industry is the biggest. It's called Nollywood.

India has --

Bollywood! Hey, we stole Bollywood.

GuruNo, no, hey, and Bollywood took it from Hollywood. But, as these Nigerian comics have been exploding, and Nollywood is growing more and more. And I'm even seeing now a lot of Netflix original productions in Nollywood. As that media is becoming more popular globally, has that changed your relationship with, like, Nigerian content or Yoruba as a language? Does it make you more invested in it now that it's starting to become more accepted?

MichaelI definitely am thinking about it more. Especially now, my mom has been watching more TV and more movies. Over COVID, I was living with my mom for almost a full year, and so we would watch stuff together, and a few times we would watch some Nollywood movies that were on Netflix like you mentioned.

And, it was interesting seeing the different types of Nollywood movies. All of them are very melodramatic. I feel like melodrama is what Nollywood kind of specializes in. But some of them were the stereotype of what a Nollywood movie is. Seven betrayals and, you know, someone cheats on their husband with the brother, and the brother's also secretly engaged to the heiress to Nigerian oil.

There's always like an heiress somewhere in there. But yeah, there's also more modern Nollywood films, like American movies I had seen, but then they had Nigerian themes. But then they also had an Internet generation tone to them. There's more diversity of type in the space than I thought. So, you know, I wanna look into more Nollywood films.

It's funny that you mentioned your mom watches more stuff now because the accessibility to Nigerian content is greater. I feel the same with my parents because -- or especially my dad -- because he pretty much exclusively watches Tamil content. And, growing up he always watched it, too, but he would always find some random site on the Internet to get that stuff. But now with the advent of Netflix, Amazon Prime, like whatever else, I think it's just really great that, like, there are just more avenues for people to, like, tap into their culture.

Disney owns Hotstar, which is like an Indian streaming service. If you have Hulu, you can access some Hotstar content. So, I was telling my dad like, "Oh, I got Hulu. I can share the login." And then he was indifferent about it. He was just like, "Oh, why are we getting this? What's the point of it?" And then I mentioned, "Oh, you can get Hotstar and then you can get Tamil movies."

I feel like it's very important that accessibility now exists because when our parents immigrated here, they were cut off from an entire world, right? And they didn't have these mediums to continue-- Aside from, yes, like they, they can like seek out spaces, like churches or, you know, whatever to get that community.

But, there are all these other mediums that were kind of lacking, at least when we were growing up. And now, 20-something years later, there's a plethora of them, which I think is really awesome. And, you know, for me, I've told you this before, it was actually through watching a lot of Tamil movies that I kind of refreshed my understanding of the language.

I feel like movies and music are a really good way to keep it constant for you. But yeah. One of the last questions, and I know you only took a little bit of time in Yoruba, but I am curious: do you have a favorite word in that language, and if so, why?

"O ti to." And that one is, "It's enough." You say that when you're just like, please stop. You know, like, "O ti to, it is enough."

Like it would almost be a game with my mom of like, anytime something would happen, we would hear her say it and it'd be like, "Oh, we know she's had enough. We need to chill."

That's awesome. Well, this has been spectacular. So, thank you so much again, Michael, for coming on this podcast. Uh, I was about to say The Passion Project, but that's not the name of this podcast.

Thanks for having me.

And that's episode two, so let's roll the credits!

I'm your host, Guru Ramanathan. This is Found in Translation. Created, executive produced, and edited by Alejandra Arevalo and myself. And music by Lux the Lightbulb. Thank you so much again for listening and embarking on this journey with us. Please like, share, comment, etc. and do all the things to help us go viral. And stay tuned for the next episode!

Thank you so much.